Technological Unemployment

I think AI will automate all, or almost all, jobs at approximately the same time. In other words, a step-change profile for the technological singularity.

Reasoning:

-

The key idea of this essay is: I think the different jobs people do are not very computationally distinct.

Being a lawyer versus being a construction worker versus being an engineer.

They seem quite distinct. That’s because, within the space of all possible computations, we’re “zoomed in” on the kinds of computations that a human can get paid to do.

Further evidence, in both humans and AIs, is what in AI is called “transfer learning”.

“Transfer learning is a machine learning method where a model developed for a task is reused as the starting point for a model on a second task.” -https://machinelearningmastery.com/transfer-learning-for-deep-learning

Humans do transfer learning too! It’s easier for an engineer to become a doctor, than it is for a random person to become a doctor.

A background in engineering helps with becoming a lawyer, even. My father is a lawyer. He said people with STEM degrees (engineering, mathematics, medicine, etc.) did very well in law school. In fact, they generally did better than people with “pre-law” degrees.

Professor Yann LeCun makes the distinction between artificial general intelligence (AGI) and “human-level intelligence”. LeCun is the head of AI at Facebook/Meta, and a Turing Award laureate (equivalent to the Nobel Prize in computer science) for his foundational work on AI.

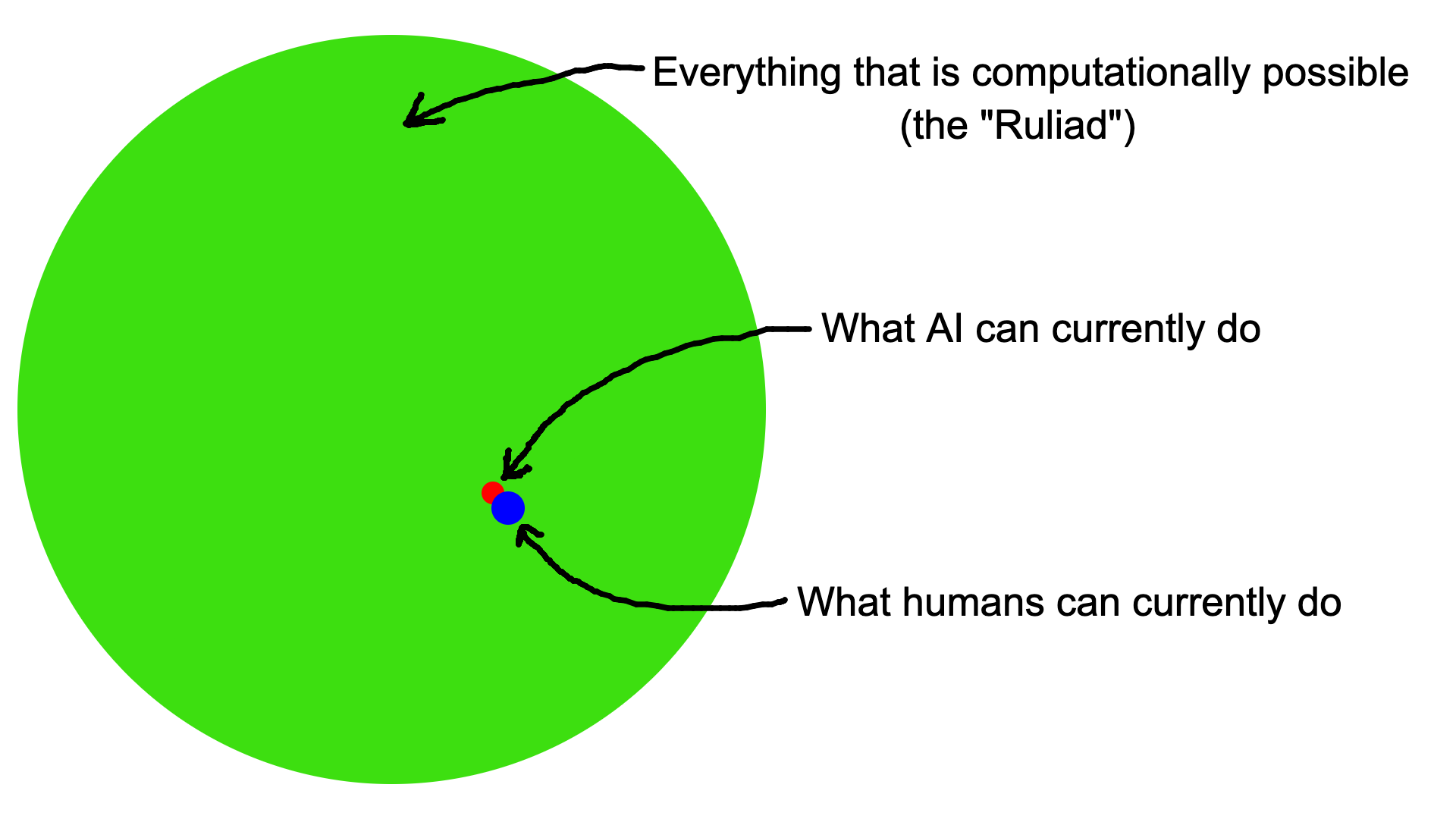

LeCun says human intelligence is actually quite narrow. In the universe of every possible computation (the “Ruliad”), human intelligence is optimized for a few specific things. That’s illustrated in the header image above. -

As far as the jobs humans have, those jobs have already been optimized around the parts of the computational universe (the Ruliad) that machines can’t handle.

People have long predicted that technological innovations, such as automobiles, would on balance destroy jobs. Spoiler: they haven’t. In fact, as we’ve automated more, there’s been more work available to be done. This is known as Jevons Paradox, named after an observation made by the English economist William Stanley Jevons in 1865. -https://news.northeastern.edu/2025/02/07/jevons-paradox-ai-future/. To quote:

British economist William Stanley Jevons first presented his eponymous paradox in his 1865 book, “The Coal Question,” where he noted that more efficient steam engines had not led to a decrease in the use of coal in British factories as many believed, but increased the use as the fossil fuel became cheaper and more engines and factories were built.

“Efficiency can backfire by making a resource so cheap that everyone uses it more,” Piao summarizes, noting that British coal consumption tripled by 1900.

Two economic theories explain this paradox:

- Joseph Schumpeter’s “Creative destruction” and

-

David Frederick Schloss’ “Lump of Labor Fallacy”

Joseph Schumpeter’s “Creative destruction” is about “the process that sees new innovations replacing existing ones that are rendered obsolete over time.”

-https://www.cmu.edu/epp/irle/irle-blog-pages/schumpeters-theory-of-creative-destruction.html

“As an example, in the late 1800s and early 1900s incremental improvements to horse and buggy transportation continued to be valuable, and innovations in the buggy and buggy whip could fetch a considerable price in the market. With the introduction of Ford’s Model T in 1908, however, these “technologies” were effectively driven out by a superior innovation. Over time, newer and better innovations will continue to drive out worse ones, just as the Model T did the horse and buggy and numerous iterations of vehicles have subsequently driven out the Model T and generations of its successors.” -https://www.cmu.edu/epp/irle/irle-blog-pages/schumpeters-theory-of-creative-destruction.html

The point is that after switching from horses to cars, there were plenty of jobs building cars, fixing cars, and so on. In fact, more jobs in total than in the era of horses.

Closely related is David Frederick Schloss’ “Lump of Labor Fallacy”.

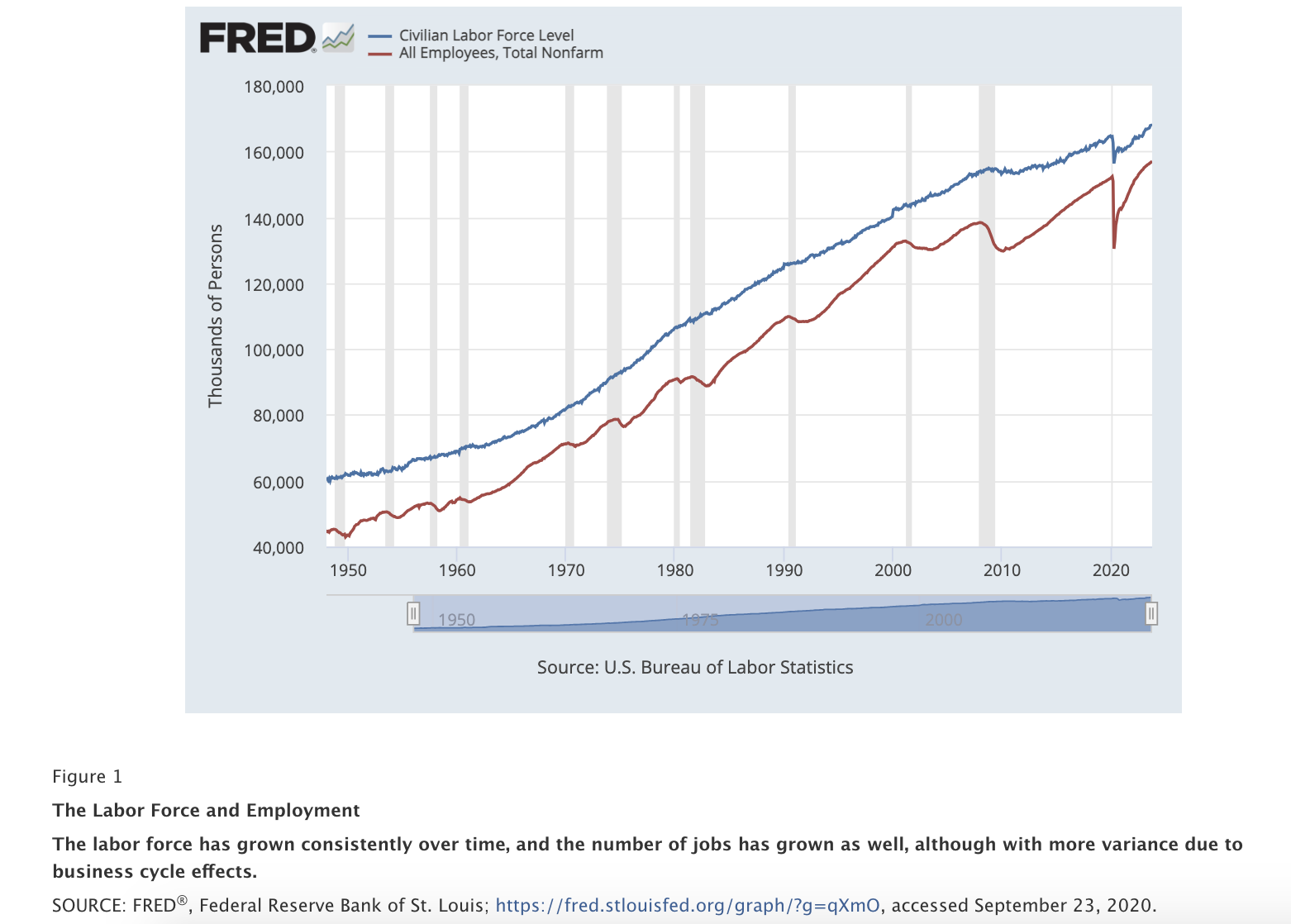

“The lump of labor fallacy is the assumption that there is a fixed amount of work to be done. If this were true, new jobs could not be generated, just redistributed. Those who believe the fallacy have often felt threatened by new technology or the entrance of new people into the labor force. These fears are rooted in a mistaken zero-sum view of the economy, which holds that when someone gains in a transaction, someone else loses. It’s a tempting idea to some because it seems to be true. For example, jobs can be lost to automation and immigration. However, that is not the full story. In reality, the demand for labor is not fixed. Changes in one industry can be offset, or overshadowed, by growth in another. And as the labor force grows, total employment increases too (Figure 1).”

-https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/page1-econ/2020/11/02/examining-the-lump-of-labor-fallacy-using-a-simple-economic-model

For a long time now, the total number of jobs, and the total number of employed people, has pretty much only gone up:

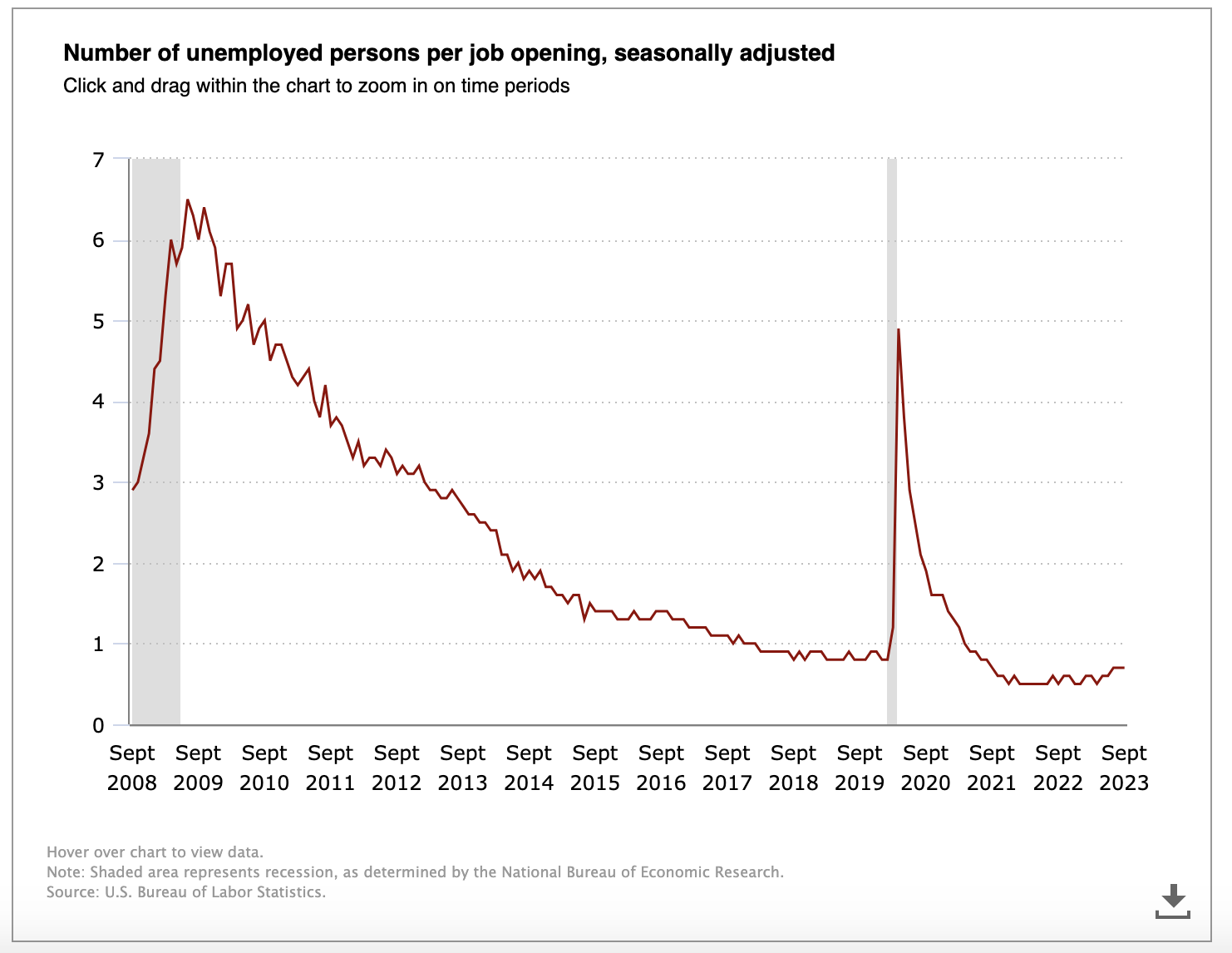

In fact, there are more job openings than unemployed people, part of a 10-year trend:

The red line going below “1” in the graph means there are more jobs than unemployed people. It’s solidly below 1 right now.

However, Creative Destruction and The Lump of Labor Fallacy aren’t laws of nature. They could stop being true any time.

“Connectionism”, however, is actual science. Connectionism is the theory that thinking, memory, and so on are all enabled by the patterns of connections between neurons in the brain.

But what does that have to do with jobs? Well, ultimately human labor boils down to patterns of connections between neurons, and the firing of those neurons. No matter how fancy or well-paid the job, it’s fundamentally just specific patterns of connected neurons firing.

Moore’s Law may as well be a law of nature, for now at least. Moore’s Law states that compute per dollar doubles every two years.

Likewise for the Chinchilla scaling laws, which guide how much data versus compute is optimal for training Large Language Models: https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.15556. -

The areas of the economy that are un-automatable tend to require what AI scientists call “grounding”. In other words, real understanding. ChatGPT isn’t grounded.

One example: ChatGPT can’t accurately multiply large numbers. That’s because it hasn’t yet in its training set seen literally every combination of large numbers being multiplied together. The amount of data it would need to see gets combinatorially explosive as the numbers get larger. The technical terminology for this is “distributional shift”. “distributional shift” is the phenomenon of the data the model is trained on being different from what it sees at inference time.

This isn’t a John Henry thing…of course you can multiply numbers with a calculator. Or you can write custom code that recognizes a given prompt as a multiplication problem and sends it to a “calculator” submodule. A calculator isn’t AGI though.

The point is LLMs don’t actually understand multiplication, much less have real models of the world. Not yet anyway.

This is similar to/a variant of Moravec’s Paradox. What’s easy for a human is hard for an AI. “It is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on intelligence tests or playing checkers, and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility” (https://lnkd.in/eetDKci6).

Fully-autonomous self-driving has been predicted for years, yet still isn’t here. The ability to use AI to augment one’s work and increase productivity is real. But that’s not replacement or the singularity. - “AI won’t replace me - I’m a plumber!”

Robotics is currently limited by software, not hardware. Skilled trades like plumbing, carpentry, and transportation, are not uniquely safe just because they don’t happen on a computer.

Check out this robot from Boston Dynamics (opens in new tab):

I think with the right software, that robot, or one like it, could install shingles on a roof. Here’s a video of a robotic hand system performing fine motor tasks via a human operator (opens in new tab):

I’m pretty sure that thing could change a faucet if it were programmed to make the correct movement. Sensors and actuators aren’t the limiting factor: software is.

As it goes for computer programming, so it goes for plumbing and carpentry. - “ChatGPT will replace all jobs”.

“ChatGPT will replace job X”.

See the above discussion of “grounding”.

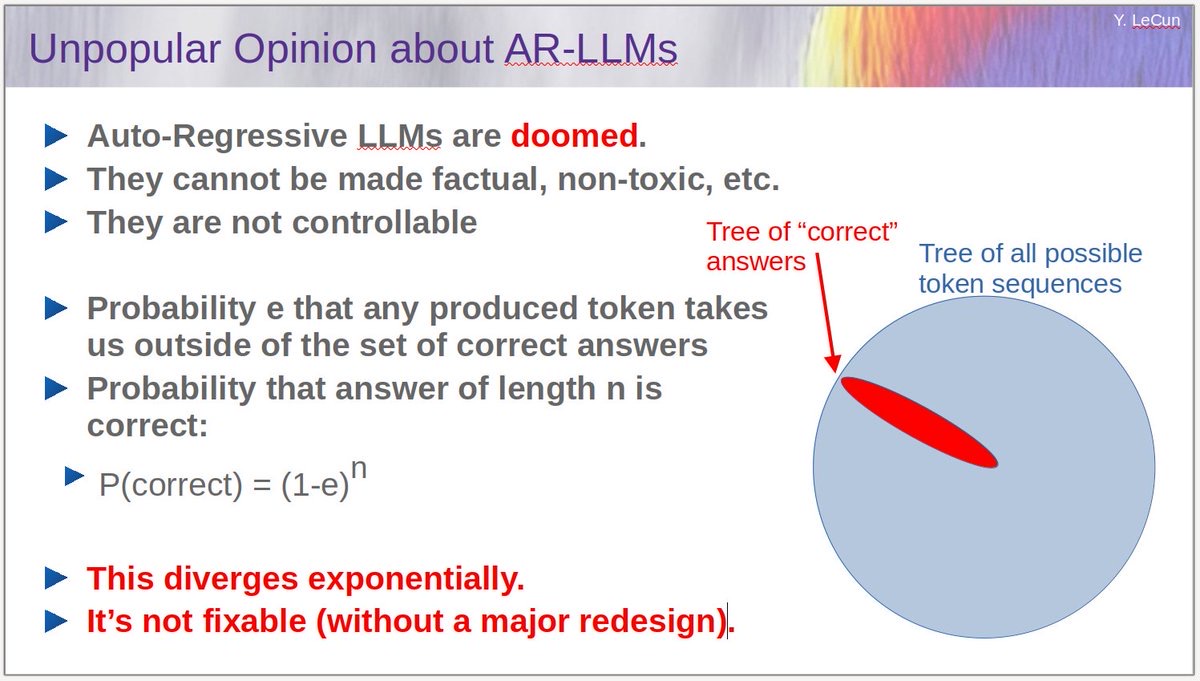

Also, large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT arguably have exponentially diminishing accuracy as Kolmogorov complexity increases. This is a post from Yann LeCun about that: https://twitter.com/ylecun/status/1640122342570336267?lang=en. This illustration from LeCun’s post is a good summary of his argument:

-

I think there will be a “technological singularity” (i.e. machines doing all jobs).

I’ve noticed lots of opinions on the matter leave it there. They say, “hey Moravec’s Paradox, real-world understanding, etc.: there is no singularity”. I disagree.

The human cortex has approximately the volume of a softball. It can’t be that hard to create human-level AI (understatement). In other words, AI will replace all jobs, but it will do so for all of them at about the same time, for the reasons described so far in this essay. Step-change. -

Coming at it from the other side, neural net architectures are converging. For example, transformers/LLMs are effective in broader and broader problem domains. Andrej Karpathy has a good thread about this: https://tinyurl.com/26vc6b36.

Google is using transformers in its robotics: https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-deepmind-rt2-robotics-vla-model/. Brains use a single architecture for all these different problem domains, why wouldn’t AI? There’s even evidence (Nature paper!) of brains doing something roughly similar to next-token prediction: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-022-01516-2. - I think the technological singularity will be a species-level cross-profession transition, with a fairly concise timeline. The question then becomes: how will humans - all of us together - handle it?